dhutaṅga

The Thirteen Ascetic Practices | The Austere Practices

dhuta

pp. of dhunāti shaken off; removed.

-2. lit. "shaken off," but always expld in the commentaries as "one who shakes off" either cvil dispositions (kilese), or obstacles to spiritual progress (vāra, nīvaraṇa).

-aṅga, a set of practices leading to the state of or appropriate to a dhuta, that is to a scrupulous person

Thus, the 13 dhutaṅgas, which mean "renunciation" [to abandon (dhuta); state of mind (aṅga)], are a set of practices designed for considerably reducing our attachments, in order to reach nibbāna at the soonest, like a bird that crosses the cloudless sky on a straight line.

The 13 ascetic practices of Buddhist monks (dhutaṅga)

These thirteen Austere Practices allowed by Lord Buddha have been characterized as a moderate and sane ascesis; they are as follows:

I. Refuse-rag-wearer's Practice (pamsukulik'anga) — wearing robes made up from discarded or soiled cloth and not accepting and wearing ready-made robes offered by householders.

II. Triple-robe-wearer's Practice (tecivarik'anga) — Having and wearing only three robes and not having additional allowable robes.

III. Alms-food-eater's Practice (pindapatik'anga) — eating only food collected on pindapata or the almsround while not accepting food in the vihara or offered by invitation in a layman's house.

IV. House-to-house-seeker's Practice (sapadanik'anga) — not omitting any house while going for alms; not choosing only to go to rich households or those selected for some other reason as relations, etc.

V. One-sessioner's practice (ekasanik'anga) — eating one meal a day and refusing other food offered before midday. (Those Gone Forth may not, unless ill, partake of food from midday until dawn the next day.)

VI. Bowl-food-eater's Practice (pattapindik'anga) — eating food from his bowl in which it is mixed together rather than from plates and dishes.

VII. Later-food-refuser's Practice (khalu-paccha-bhattik'anga) — not taking any more food after one has shown that one is satisfied, even though lay-people wish to offer more.

VIII. Forest-dweller's Practice (Araññik'anga) — not dwelling in a town or village but living secluded, away from all kinds of distractions.

IX. Tree-root-dweller's Practice (rukkhamulik'anga) — living under a tree without the shelter of a roof.

X. Open-air-dweller's Practice (abbhokasik'anga) — refusing a roof and a tree-root, the practice may be undertaken sheltered by a tent of robes.

XI. Charnel-ground-dweller's Practice (susanik'anga) — living in or nearby a charnel-field, graveyard or cremation ground.

XII. Any-bed-user's Practice (yatha-santhatik'anga) — being satisfied with any dwelling allotted as a sleeping place.

XIII. Sitter's Practice (nesajjik'anga) — living in the three postures of walking, standing and sitting and never lying down.

With Robes and Bowl: Glimpses of the Thudong Bhikkhu Life by

Bhikkhu Khantipalo

The benefits

Those who put the dhutaṅgas into practice derive a large number of benefits. There are general benefits, such as a significant reduction of the following: attachments, greed, household chores, occasions to breach the pātimokkha rules, and the suffering of enduring discomfort. In addition, there are the benefits peculiar to the specific dhutaṅgas: 1) absence of attachment to clothes; 2) reduction of household tasks; 3) the establishment of a link between the saṃga and lay society; 4) certainty of eating only food offered

correctly; obligation to sustain attention; 5) reduced greed, gain of time and clarity of mind, reduced digestion; 6 et 7) help to concentration, decreased attachment to food, better management of one’s food rations; 8) protection against urban distractions, tranquillity; 9, 10 and 11) complete independence with regard to lodging, suppression of opportunities to develop attachment to comfort or luxury, total freedom; 12) development of the capacity to accept things as they come; 13) suppression of sloth, vigilance, nobility.

In general, the dhutaṅgas tend to reduce mental impurities (kilesās).

PDF: The Manual of the Bhikkhu by Venerable Dhamma Samit, pg 97

The true beauty of a dhutanga monk lies with the quality of his practice and the simplicity of his life. When he dies, he leaves behind only his eight basic requisites – the only true necessities of his magnificent way of life. While he’s alive, he lives majestically in poverty – the poverty of a monk. Upon death, he is well-gone with no attachments whatsoever. Human beings and devas alike sing praises to the monk who dies in honorable poverty, free of all worldly attachments. So the ascetic practice of wearing only the three principal robes will always be a badge of honor complementing dhutanga monks.

Ācariya Mun was conscientious in the way he practiced all the dhutanga observances mentioned above. He became so skillful and proficient with them that it would be hard to find anyone of his equal today. He also made a point of teaching the monks under his tutelage to train themselves using these same ascetic methods. He directed them to live in remote wilderness areas, places that were lonely and frightening: for example, at the foot of a tree, high in the mountains, in caves, under overhanging rocks, and in cemeteries. He took the lead in teaching them to consider their daily almsround a solemn duty, advising them to eschew food offered later. Once lay devotees in the village became familiar with his strict observance of this practice, they would put all their food offerings into the monks’ bowls, making it unnecessary to offer additional food at the monastery. He advised his disciples to eat all food mixed together in their bowls, and to avoid eating from other containers. And he showed them the way by eating only one meal each day until the very last day of his life.

Since the moral quality of any action depends entirely upon the accompanying intention and volition, this is also the case with these ascetic practices, as is expressly stated in Vis.M. Thus the mere external performance is not the real exercise, as it is said (Pug. 275-84): "Some one might be going for alms; etc. out of stupidity and foolishness - or with evil intention and filled with desires - or out of insanity and mental derangement - or because such practice had been praised by the Noble Ones...." These exercises are, however properly observed "if they are taken up only for the sake of frugality, of contentedness, of purity, etc." (App.)

dhutānga | Manual of Buddhist Terms and Doctrines,

by Nyanatiloka

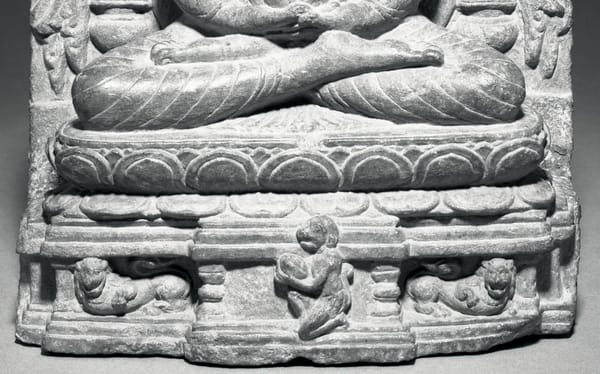

A bronze ascetic Buddha figure, Thailand, early 19th century