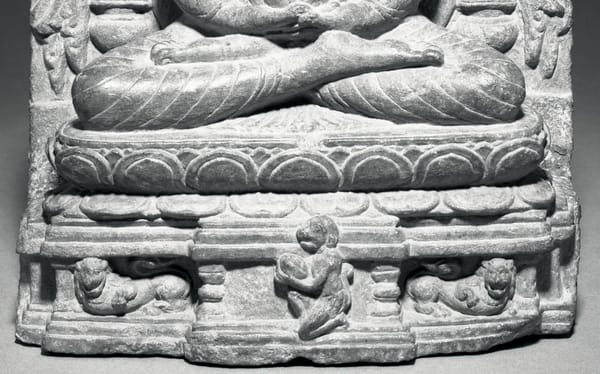

1st to mid-2nd century

This small bronze Buddha is probably one of the earliest iconic representations of Shakyamuni from Gandhara. He sits in a yogic posture holding his right hand in abhaya mudra (a gesture of approachability); his unusual halo has serrations that indicate radiating light. His hairstyle, the form of his robes, and the treatment of the figure reflect stylistic contacts with the classical traditions of the West. This Buddha shows closer affinities to Roman sculpture than any other surviving Gandharan bronze.

Date: 1st to mid-2nd century

Culture: Pakistan (ancient region of Gandhara)

Medium: Bronze with traces of gold leaf

Dimensions: H. 6 5/8 in. (16.8 cm); W. 4 1/2 in. (11.4 cm); D. 4 in. (10.2 cm)

Classification: Sculpture

Credit Line: Gift of Muneichi Nitta, 2003

Accession Number: 2003.593.1

Seated Buddha | Pakistan (ancient region of Gandhara) | The Met

Alexander the Great (d. ca. 323 b.c.) left a legacy of strong links to the classical world in the ancient region of Gandhara, today within the borders of Pakistan and Afghanistan. Reinforced by subsequent rulers and continued contact through editerranean trade, this legacy led to a Gandharan style of art dependent upon Hellenistic and Roman prototypes. Other influences contributed to this style, but the classical flavor of Gandharan sculpture under the Kushans (r. 1st-3rd century) is strong and unmistakable. The iconography, however, is almost completely Buddhist, resulting in a marriage that makes Gandharan art unique.

Gandharan sculptural styles are well preserved by rich remains in stone and stucco. A few rare small bronze images of the Buddha, usually following styles in stone, have also survived. The earliest and most important is this seated Buddha from the Nitta collection, often published and of incalculable importance to the early history of the Buddha image. No other Asian Buddha owes so strong an allegiance to classical prototypes. Rather than following styles of early Gandharan stone Buddhas, it closely follows that of Roman portrait sculptures.

The Buddha sits in the cross-legged yogic posture of vajraparyankasana, with the soles of both feet facing upward. His right hand makes the fear-allaying abhayamudra; his left holds part of his robe. The heavy folds of the garment are atypical for Gandhara. The Buddha's hair is in a bun on top of wavy locks, and he has a mustache. Behind his head there is an unusual spoked halo.

A sculpture in the Metropolitan's collection that is particularly important to the debate surrounding the development of devotional imagery in Gandhara is a bronze representation of the Buddha Shakyamuni (no. 39). This relatively small statue has traces of gilding in the halo and robes, so it would originally have looked quite different from the way it does now. The Buddha is shown seated in a yogic posture, holding his hand in abhaya mudra, and the halo surrounding his head has serrations that indicate radiating light. His robe falls in gentle folds and covers both shoulders, unlike the Mathuran image, in which the fabric covers only one shoulder. The Mathuran seated Buddha exposes and calls attention to Shakyamuni's perfect and enlightened body, whereas the Gandharan sculpture emphasizes the drapery.

It is possible that the Gandharan statuette of Shakyamuni dates to as early as the first century A.D., judging by what some scholars have described as its "raw and unassimilated" Greco-Roman influence; indeed, the figure shows numerous connections with Roman imperial portraits of the first century A.D., especially those of Nero, in its close-set eyes, prominent ears, and forward-combed hair that falls in a C shape of curls across the forehead. By the first century A.D. Gandharan artists had been working in classical styles for more than three hundred years, however, so it is problematic to date the sculpture solely on this basis. Moreover, the portrait form that evidently influenced the creation of this statue might have been centuries old by the time it reached Gandhara. Yet there are other aspects of the image that do suggest that it was made in the first or second century A.D. First, the serrated halo is found on coins minted from about the first century B.C. to the third century A.D., but it is not seen in other Gandharan images of the Buddha, indicating that it was made in an earlier period, during what was perhaps a time of experimentation.' Second, the Gandharan Buddha and the dated Mathuran Buddha have some specific features in common; for example, the lotuses on the hands and feet of the Gandharan Buddha correspond to the wheels and triratna (three jewels) on the hands and feet of the Mathuran image, something rarely seen in other Gandharan images. The artist who cre-ated the bronze Gandharan Buddha also reversed the feet, a mistake unlikely to have been made in a period when the production of Buddha images was well established and widespread. For these reasons, it seems likely that this sculpture is an example of Gandharan production that probably dates to no later than the mid-second century A.D., or to about the same time as the Mathuran example. It should be noted, however, that the stylistic origins of the Gandharan Buddha appear to be very different from that of the devotional icons produced in the Mathura region, where images of yakshas (male protective deities) laid the ground-work for the emergence of iconic Buddha images.

Comparing the Metropolitan's seated bronze Buddha with those depicted in Gandharan narrative reliefs such as the Buddha delivering the first sermon in number 34, which shows a developed notion of the Buddha image—raises the question of whether the earliest anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha made in Gandhara were iconic or narrative. If Gandharan anthropomorphic images of the Buddha first developed in narrative contexts, and the idea of iconic imagery emerged from that core, then this small seated bronze, which seems to have been produced at about this crucial moment, may be one of the earliest surviving Gandharan devotional icons.