Ajanta

The Greatest Ancient Picture Gallery by William Dalrymple | The New York Review of Books

The Ajanta murals told the Jataka stories of the lives of the Buddha in images of supreme elegance and grace. Unlike the flatter art of much later Indian miniature painting, here the artists used perspective and foreshortening to produce paintings of courtly life, ascetic renunciation, hunts, battles, and erotic dalliance that rank as some of the greatest masterpieces of art produced by mankind in any century.

Twenty-two years later, in 1866, the great Indian Uprising of 1857 had come and gone, the vengeful British had murdered hundreds of thousands of suspected rebels, the East India Company had been removed from power, and instead Queen Victoria had been proclaimed empress of a now fully colonized India—but Major Gill was still in his beloved caves, hard at work. When he finally sent his painstakingly detailed oil paintings to London for exhibition in 1866 at the Crystal Palace, they were almost immediately destroyed in the fire that engulfed the exhibition center. Tragically, the paintings had not even been photographed. Gill knew what he had to do: with astonishing sangfroid, he packed his bags and returned to the site to begin work again. He died there, still absorbed by his copying, in 1875.

Doorway of Buddhist Vihara, Cave XXIV, Ajanta, with Major Gill seated in entry

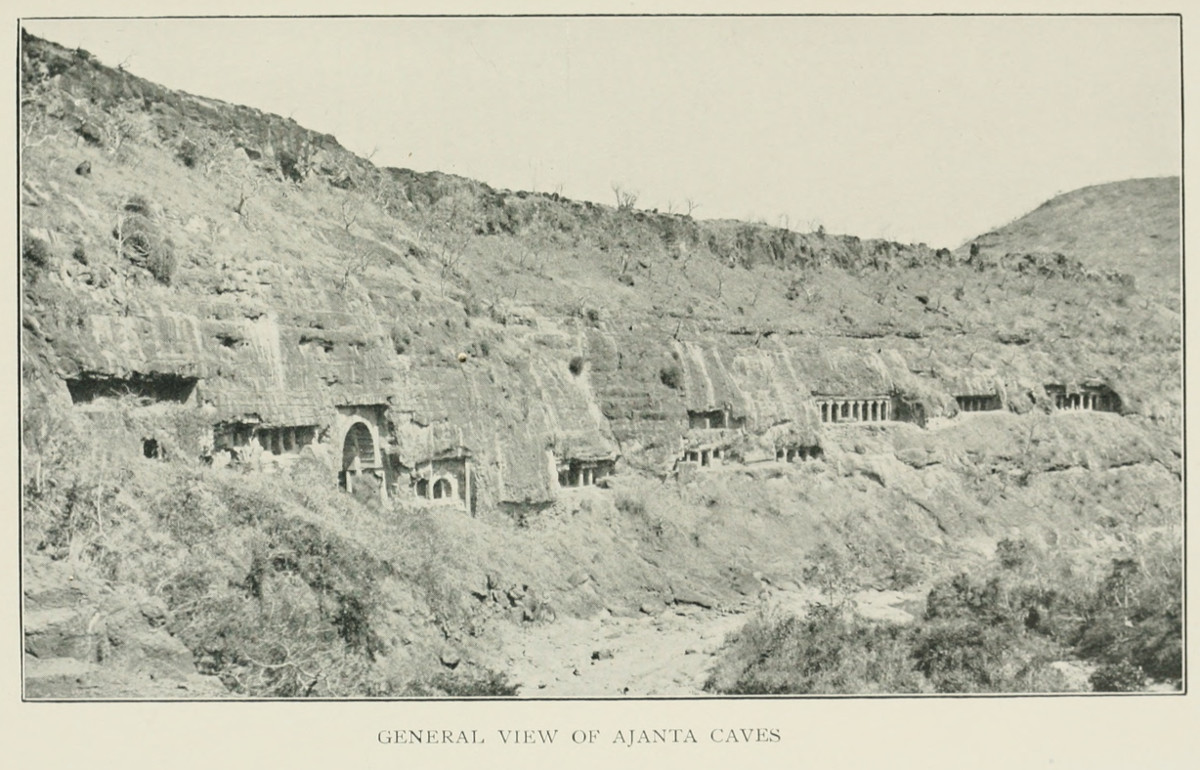

Archaeological Survey of India - Ajanta

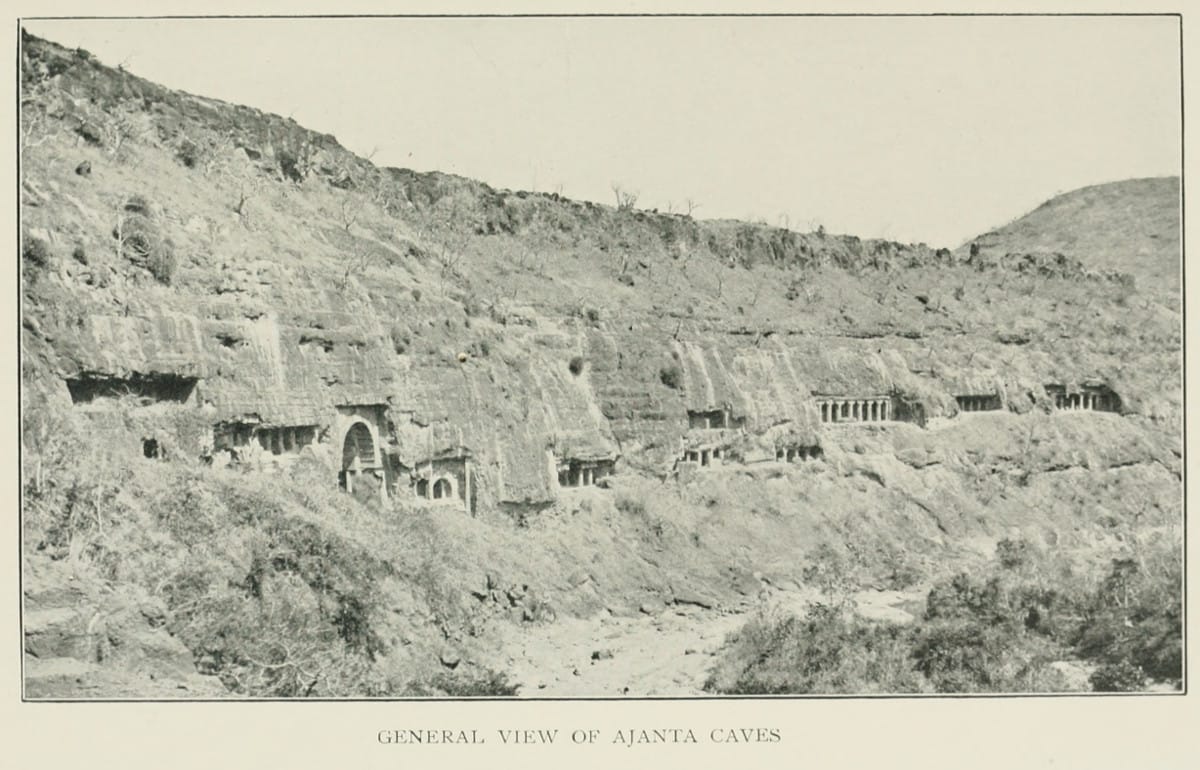

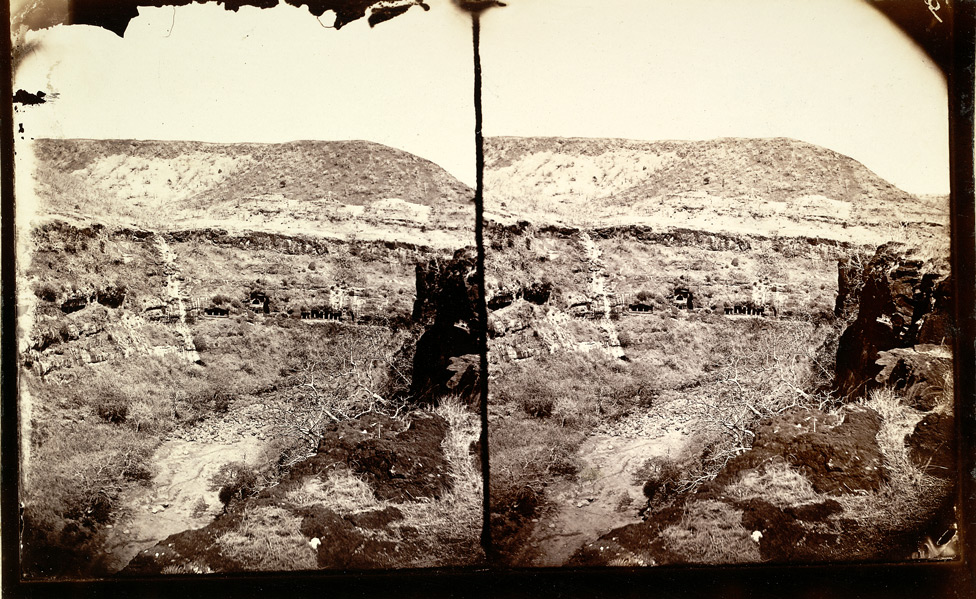

Stereoscopic General view of upper caves from stream, Ajanta, 1868

From Footfalls of Indian History by Sister Nivedita, 1915

Interior of Buddhist chaitya hall, Cave IX, Ajanta 10004482, 1869

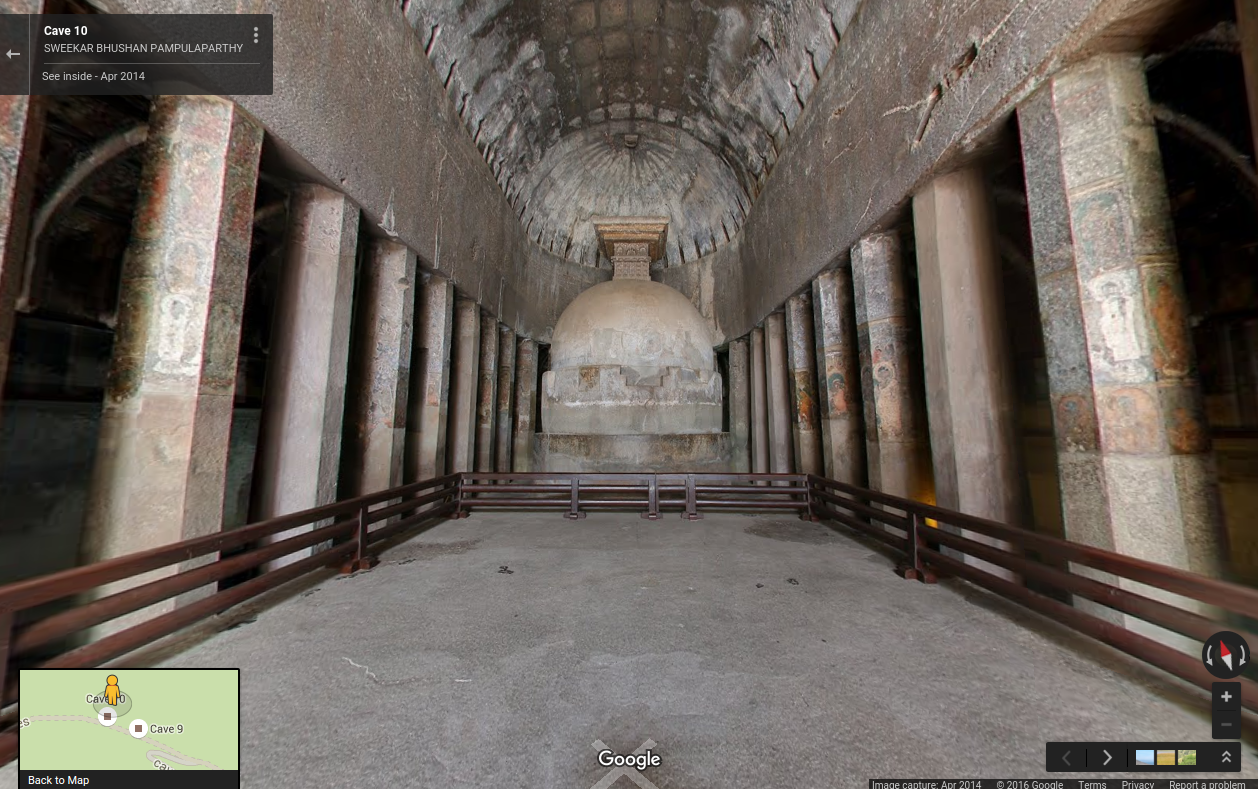

Interior of Buddhist chaitya hall, Cave X, Ajanta 10004483, 1869

Cave 10 via Google Street View

Interior of Buddhist chaitya hall, Cave XXVI, Ajanta, 1869

Cave 26 via Google Street View