Mes Aynak

In the spring of 1963, a French geologist set out from Kabul to carry out a survey in Logar province in eastern Afghanistan. His destination was the large outcrop of copper-bearing strata in the mountains above the village of Mes Aynak. But in the course of boring for samples, the geologist stumbled on something much more exciting: an entire buried Buddhist city dating from the early centuries AD. The site was clearly very large – he estimated that it covered six sq km – and, although long forgotten, he correctly guessed that it must once have been a huge and wealthy terminus on the Silk Road.

Mes Aynak: Afghanistan's Buddhist buried treasure faces destruction | The Guardian

Among the works of art rescued from destruction are the oldest known complete wooden Buddha (left), eight inches tall, and a painted clay figure of a rich female monastery patron, 32 inches tall. Both date from around A.D. 400 to 600.

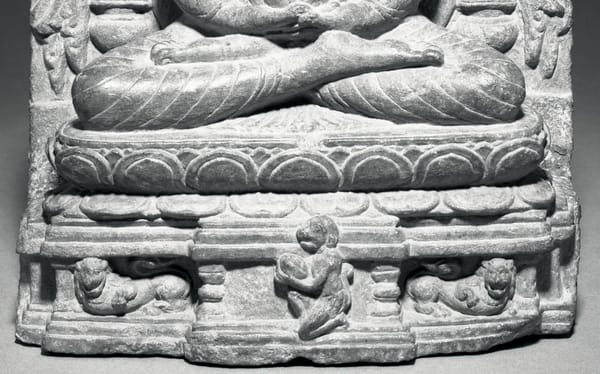

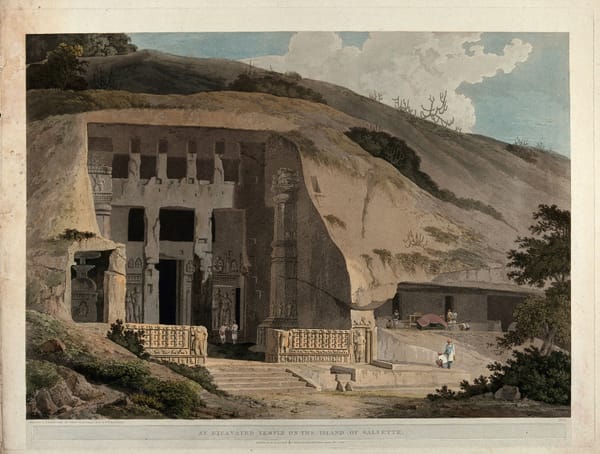

Mes Aynak was a spiritual hub that flourished in relative peace. At least seven multistory Buddhist monastery complexes, containing chapels, monks’ quarters, and other rooms, form an arc around the site, each protected by ancient watchtowers and high walls. Within these fortified complexes and residences the archaeologists have uncovered nearly a hundred schist and clay stupas, Buddhist reliquaries that were central to worship. The stupas range in size from monumental to easily portable.

Mes Aynak was also a key economic center in Gandhara, a region spanning what’s now eastern Afghanistan and northwestern Pakistan. Gandhara was a civilizational crossroads, a place where the great religions of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Zoroastrianism met and where ancient Greek, Persian, Central Asian, and Indian cultures melded. It was the “center of the world,” in the words of Abdul Qadir Temory, the lead Afghan archaeologist on the project.

In the first centuries A.D. the Gandharan Buddhists revolutionized the region’s art, refining an aesthetic sensibility that had synthesized the vestiges of earlier centuries of conquest. They were among the first artists in the world to depict the Buddha in realistic, human form—a Hellenistic innovation from the days of Alexander the Great, who first marched through Afghanistan in 330 B.C. At Mes Aynak chapels have been uncovered with double-life-size Buddha statues still bearing traces of their red, blue, yellow, and orange painted robes; caches of gold jewelry; fragments of ancient manuscripts; and walls adorned with frescoes.

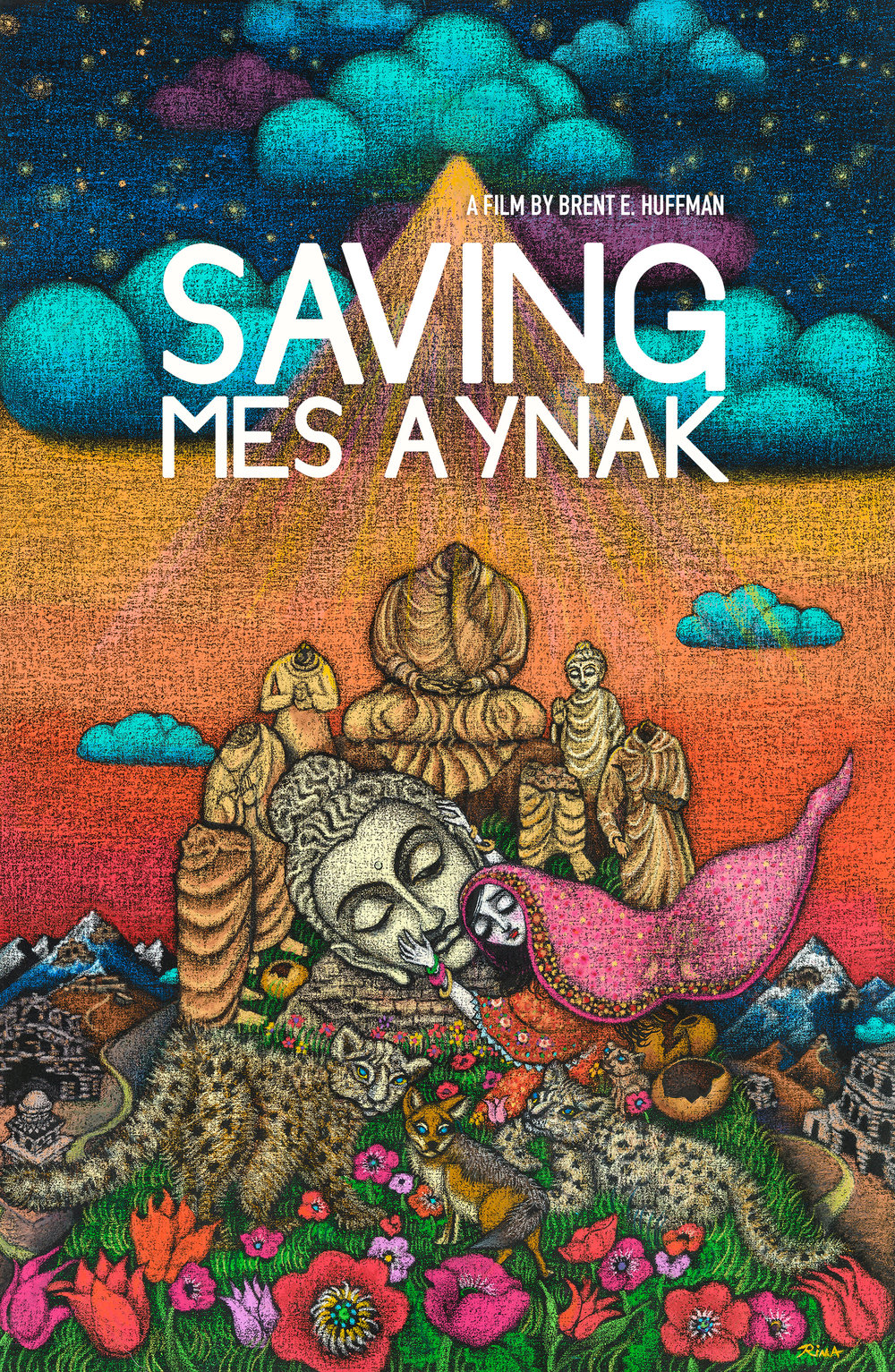

The award-winning film SAVING MES AYNAK follows archaeologist Qadir Temori as he races against time to save a 5,000-year-old Buddhist archeological site in Afghanistan from imminent demolition by a Chinese State-owned mining company, who plan to destroy Mes Aynak to mine for $100 billion worth of copper.

Saving Mes Aynak - Al Jazeera English

As the United States and NATO prepare to scale down their mission in Afghanistan, and with it the massive international funding that has essentially been subsidizing the country and its government for the last ten years, the country has appeared to face a tragic choice. It truly possesses rich mineral resources. But due to its ancient history, these typically lie under priceless archaeological remains. Mes Aynak, where the Chinese company MCC obtained the contract to mine copper, perfectly represents this dilemma. Copper is extremely lucrative – but how do you put a price on a 5000 year old buried city containing multiple monasteries and settlements possibly going back to the Bronze Age, a site at least as significant as the tragically lost Buddhas of Bamiyan?

Are culture and commerce here locked into a zero sum game? Or can there be a way forward that gives both their due?

Unfortunately, Huffman's film profoundly misrepresents the situation, offers no solution and is likely to do more harm than good. Huffman claims that mining is scheduled to start at the end of this year, and that this will spell the end of the buried city. The way to prevent this is to support his indiegogo campaign and fund distribution of his film, which will create an international uproar and cause the Afghan government to halt the mining. This storyline is almost entirely false.

Crying Wolf | ARCH International

Saving Mes Aynak shows the sheer determination of the Afghan archaeologists to protect their culture against overwhelming odds. ‘We are all one. We must join together and raise our voices to spread awareness around the world,’ Qadir insists.

Huffman has crafted a remarkable film of courage, heroism, and hope. And the fight is not yet over: ‘Cultural heritage goes in tandem with human rights. Erasing a country’s history is a terrible crime. There is still a chance to save the site, and now is the moment to spread the word.’

Saving Mes Aynak | World Archaeology

That underground wealth, as much as $1 trillion by some estimates, offers one of Afghanistan's best hopes for standing on its own financially when the U.S.-led military coalition withdraws most troops and much of its aid by the end of 2014.

Besides the copper deposit at Mes Aynak, which a Chinese consortium has pledged to invest $3.5 billion to develop, Afghanistan has awarded rights to extract iron ore, gold and oil, to companies from India, Canada, the U.S. and Britain.

The Mes Aynak project offers a warning of how difficult it is likely to be for Afghanistan to cash in on its mineral wealth. Delays in the now five-year-old project threaten to deprive a fragile Afghan state of a crucial revenue stream when it will be most needed, in the first years after the U.S. and its allies withdraw most of their military forces.

Delays Imperil Mining Riches Afghans Need After Pullout - WSJ

The team of archaeologists working to preserve Mes Aynak uncovered a life-size gilded plaster head of the Buddha (left). A laborer on the team is shown at right.